Over July and August I’m carrying out a series of research visits to three UK public art ‘collections’ as part of my PhD fieldwork. The first of these visits took me down to Milton Keynes. This is a place I’d certainly read quite a lot about in terms of its cultural geography [1, 2, 3] but never actually visited before. Milton Keynes is famous as the UK’s largest and, for some, most successful ‘new town’. It was built in the late 1960s to a radical modernist design that has been described as something of a meeting between the futurism of American architect Buckminster Fuller and the romanticism of the English ‘Garden City’. For some its original design (led by architect and town planner Derek Walker) is still seen as visionary, one of the great unsung projects of British post-war design. For others the town is a characterless, ‘brutalist wasteland’ [4], and a ‘Mecca for roundabouts’[5].

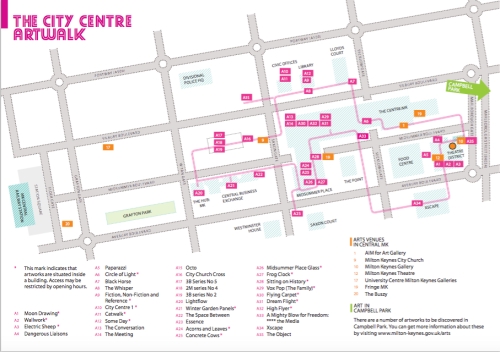

Unusually in the UK, Milton Keynes is also a town that actively promotes itself as having a ‘public art collection’: the reason for my research visit. This is a collection that encompasses some 220 permanent artworks located across the city centre and its wider area. I was only able to visit a small proportion of these during my visit, concentrating on the works located in the centre of Milton Keynes that feature in the city’s official ‘City Centre Artwalk’ booklet.

Starting from the ‘Theatre District’ this route led me in a looping circuit around the central grid of Milton Keynes. This encompasses the town’s main commercial, retail and civic hub situated between the parallel tree-lined ‘Boulevards’ – the romantically (paganly?) named ‘Avebury’, ‘Midsummer’ and ‘Silbury’ – and their intersecting ‘Gates’. For a visitor, and public art researcher, like me one of the most striking features of this route is the way in which the public art walk threads between outdoor street space and the interior ‘malls’ of its main shopping centre ‘The Centre: MK’ and the adjoining (now listed) ‘Midsummer Place’. Two of Milton Keynes most locally popular artworks are sited within these malls: ‘Vox Pop (The Family)’ and a small herd of Liz Leyh’s original ‘Concrete Cows’ (sometimes cynically described as a symbol of MK’s all-pervasive ‘concreteness’).

‘Vox Pop (The Family), John Clinch, 1988. According to the Artwork Guide Clinch’s sculpture ‘celebrates ordinary members of the public rather than the rich and famous’. It was ‘originally intended to show the diversity of people needed to make Milton Keynes a great city’.

‘Concrete Cows’. These are the ‘original’ concrete cows created by resident MK artist Liz Leyh and local schoolchildren in 1978. These are now corralled around the remains of the town’s celebrated oak tree in the middle of the Midsummer Place shopping mall.

Other mall-based public artworks include a humorous bronze ‘book’ bench by Bill Woodrow (outside Waterstones), ‘Circle of Light’ by US born kinetic artist Liliane Lijn (a work which I was looking for but somehow managed to miss in my walk round), and a series of fantastical bronzes by British sculptor Philomena Davis. These are located in ‘Silbury Arcade’, alongside branches of Carphone Warehouse, Claire’s, and Patisserie Valerie. Together these mall-sited works are striking examples of the way the viewing (visuality) of public artworks is often enmeshed within the urban retail experience: an ingredient of urban visuality and ‘aestheticisation’ that has been specifically highlighted in reference to Milton Keynes [6].

‘High Flyer’ one of three bronzes by Philomena Davis sited in Silbury Arcade. According to the artist these works ‘depict man’s fantasy with flight and escapism, in particular….that come to us in childhood and adolescence’. According to the on-site label the sculpture is modelled on one of the artist’s own children.

Exploring beyond the polished spaces of the shopping mall the outdoor streetscape of Milton Keynes felt like a very different material and visual environment for public art. Away from the brightness of the newer retail and leisure developments this is a less manicured and much more worn space. One that is open to the elements and that feels both concrete and green. The aesthetic here would seem to echo that of the sculpture ‘court’ or the ‘sculpture park’, albeit often on a pocket scale and in a rougher urban form. My public art route took me through a number of such spaces. A rather neglected public seating area/walkway between a branch of Wallis and one of the main Boulevards held an energetic (‘Vorticist’ inspired?) bronze by Michael Sandle: the radically titled, ‘A Mighty Blow for Freedom:****the Media’, while a trio of abstract and colourful sculptures by artist/designer Bernard Schottlander dominated the dried out summer lawn and patio of the park leading up to the City Church.

‘A Mighty Blow for Freedom: ****the Media’, Michael Sandle, 1988. The Artwalk Guide tells me that the work is a twist on a well known film company logo, here replacing the famous image of the gong sounder with a man swinging an axe into a television.

Two sculptures from the ‘3B’ and ‘2M’ series. Simple forms which, according to the MK public art guide, are a play on the artist’s initials: BMS.

‘The Object’ Dhruva Mistry, 1995-7, tucked away in its own pocket ‘sculpture park’ near Milton Keynes Gallery.

Beyond this artwork and once through the strange under-croft of the motorway Milton Keynes centre opens up into green space proper – Campbell Park and its outlook to the wider rural landscape beyond. This too contains a number of sculptures, many of these dating from the 1990s but also some newer works commissioned as part of the Campbell Park Public Art Plan . The latest of these is the ‘MK Rose’ the final artwork I visited as part of my Milton Keynes public art fieldtrip.

The ‘MK Rose’ by Gordon Young is designed as a new communal and commemorative space for Milton Keynes. It is a physical ‘calendar of days’ represented by 105 pillars each dedicated to a different day of celebration or commemoration, some national and some local to Milton Keynes. The work was commissioned by the Milton Keynes Cenotaph Trust and the Milton Keynes Parks Trust.

References:

[1] Massey, D. & Rose, G., 2003. Personal Views: Public Art Research Project.

[2] AMH, 2006. Public Art in Milton Keynes Street Survey.

[3] Basdas, B., Degen, M. & Rose, G., 2009. Learning about how people experience built environments,

http://ixia-info.com/new-writing/learning-about-how-people-experience-built-environments/

[4] Voices, P. et al., 2015. Concrete bungle : Exhibition of history of Milton Keynes fails to capture flawed urban experiment Milton Keynes deserves more than a PR version of its futuristic roots. , (July).

[5] Independent, S.T., 2015. Derek Walker : Architect and planner who designed Milton Keynes dies aged 85. , (July).

[6] Degen, M., DeSilvey, C. & Rose, G., 2008. Experiencing visualities in designed urban environments: Learning from Milton Keynes. Environment and Planning A, 40(8), pp.1901–1920.